Fraud, Misrepresentation and Mistake under Indian Contract Act

FRAUD According to section 17 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 “FRAUD” means and includes any of the following acts committed by a party to a contract, or by his agent, with intent to deceive another party thereto or his agent, or to induce him to enter into the contract: The suggestion, as a fact, of that which is… Read More »

FRAUD According to section 17 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 “FRAUD” means and includes any of the following acts committed by a party to a contract, or by his agent, with intent to deceive another party thereto or his agent, or to induce him to enter into the contract: The suggestion, as a fact, of that which is not true, by one who does not believe it to be true; The active concealment of a fact by one having knowledge or belief of the fact; A promise made without any intention...

FRAUD

According to section 17 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 “FRAUD” means and includes any of the following acts committed by a party to a contract, or by his agent, with intent to deceive another party thereto or his agent, or to induce him to enter into the contract:

- The suggestion, as a fact, of that which is not true, by one who does not believe it to be true;

- The active concealment of a fact by one having knowledge or belief of the fact;

- A promise made without any intention of performing it;

- Any other act fitted to deceive;

- Any such act or omission as the law specially declares to be fraudulent.

Explanation – Mere silence as to facts likely to affect the willingness of a person to enter into a contract is not fraud, unless the circumstances of the case are such that, regard being had to them, it is the duty of the person keeping silence to speak, or unless his silence is, in itself, equivalent to speech.

ESSENTIALS OF FRAUD

According to Section 17, following are the essentials of Fraud:-

- There should be a false statement of fact by a person who himself does not believe the statement to be true.

- The statement should be made with a wrongful intention of deceiving another party thereto and inducing him to enter into the contract on that basis.

False statement of fact [SECTION17 (1)]

- In order to constitute fraud, it is necessary that there should be a statement of fact which is not true. Mere expression of opinion is not enough to constitute fraud.

- For example – A person, who is aged over 60 years and thus beyond insurable age, deliberately makes a false statement that his age is 48 years in order to take out an insurance policy, it amounts to fraud, and the insurer is entitled to avoid the policy.

In Edington vs. Fitzmaurice[1], a company was in great financial difficulties and needed funds to pay some pressing liabilities. The company raised the amount by the issue of debentures. While raising the loan, the directors stated that the amount was needed by the company for its development, purchasing assets and completing buildings. It was held that the directors had committed a fraud.

Mere silence is no fraud

It has been noted above that to constitute fraud; there should be a representation as to be certain untrue facts. Active concealment has also been considered to be equivalent to a statement because in that case, there is a positive effort to conceal the truth and create an untrue impression on the mind of the other. Mere silence, however, as to facts in no fraud. Explanation to “section 17”, in this connection, incorporates the following provision:

“Mere silence as to facts likely to affect the willingness of a person to enter into a contract is not fraud, unless the circumstances of the case are such that, regard being had to them, it is the duty of the person keeping silence to speak, or unless his silence is, in itself, equivalent to speech”.

In KEATES vs. LORD CADOGAN[2], A let his house to B which he knew was in ruinous condition. He also knew that the house is going to be occupied by B immediately. A didn’t disclose the condition of the house to B. It was held that he had committed no fraud.

In SHRI KRISHAN vs. KURUKSHETRA UNIVERSITY[3], Shri Krishan, a candidate for the L.L.B. part1 exam, who was short of attendance, did not mention that fact himself in the admission form for the examination. Neither the head of the law department nor the university authorities made proper scrutiny to discover the truth. It was held by SC that there was no fraud by the candidate and the university had no power to withdraw the candidate on that account.

EXCEPTIONS:-

- When there is a duty to speak, keeping silence is fraud.

- When silence is, in itself, equivalent to speech, such silence is a fraud.

DUTY TO SPEAK ( Contracts Uberrima Fides)

When the circumstances of the case are such that, regard being had to them, it is the duty of the person keeping silence to speak, keeping silence in such a case amounts to fraud. When there is a duty to disclose facts, one should do so rather than to remain silent.

In LIFE INSURANCE CORPN. OF INDIA V. ASHA GOEL[4], the apex court explained:

The contracts of insurance including the contract of life insurance uberrima fides and every fact of material must be disclosed, otherwise, there is good ground for rescission of the contract. The duty to disclose material facts continues right up to the conclusion of the contract and also implies any material alteration in the character of risk which may take place between the proposal and acceptance. If there are any misstatements or suppression of material facts, the policy can be called into question. For determination of the question whether the suppression relates to a fact which is in the exclusive knowledge of the person intending to take the policy and it could not be ascertained by a reasonable inquiry by a prudent person.

Marital status – Non-disclosure

Non-disclosure of material facts relating to parties to the marriage has been held to constitute fraud within the meaning of section 17 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

In KIRAN BALA vs. BHAIRE PRASAD SRIVASTAVA[5], first marriage of the appellant, Kiran Bala, had been annulled on the ground that she was of unsound mind at the time of that marriage. She was married to the respondent, Bhaire Prasad Srivastava, the second time. The fact of the annulment of the first marriage on the ground that she was an idiot was not disclosed to the bridegroom either by the girl or her parents. It was held that it was not the duty of the bridegroom to find out these facts, but it was the duty of the girl or her parents not to conceal these facts. Consent of the bridegroom was held to have been obtained by fraud, and the second marriage of the appellant with respondent was, therefore, annulled by a decree under section 12(1) (c) of the HINDU MARRIAGE ACT.

SILENCE BEING EQUIVALENT TO SPEECH

Sometimes keeping silent as to certain facts may be capable of creating an impression as to the existence of a certain situation. In such a case, silence amounts to fraud.

Means of discovering the truth

“If such consent was caused by misrepresentation or by silence fraudulent within the meaning of section 17, the contract, nevertheless, is not voidable, if the party whose consent was so caused had the means of discovering the truth with ordinary diligence”

In SHRI KRISHAN vs. KURUKSHETRA UNIVERSITY[6], Shri Krishan, a candidate for the L.L.B. part 1 examination of the university did not complete the prescribed number of lectures which could make him eligible for appearing in the examination. He, however, filled the examination form for appearing in the examination without mentioning the fact that his attendance was short. The university authorities could have discovered the truth by proper scrutiny. The university wanted to cancel the candidature of the candidate on the ground of fraud. It was held that there was no fraud as the candidate has just kept silent as to certain facts and further, the university authorities could have discovered the truth with ordinary diligence.

ACTIVE CONCEALMENT [section 17(2)]

When there is an active concealment of a fact by one having knowledge or belief of the fact, that can also be considered to be equivalent to a statement of fact, that can also be considered to be equivalent to a statement of fact and amount to fraud. By active concealment of certain facts, there is an effort to see that the other party is not able to know the truth and he is made to believe as true which is in fact not so.

Example: A is entitled to succeed to an estate at the death of B. ‘B’ dies. C having received intelligence of B’s death, prevents the intelligence reaching ‘A’ and thus induces A to sell him his interest in the estate. The sale is voidable at the option of A.

PROMISE MADE WITHOUT ANY INTENTION TO PERFORM IT [section 17(3)]

When a person makes a promise, there is deemed to be an undertaking by him to perform it. If there is no such intention when the contract is being made, it amounts to fraud. Thus, if a man takes a loan without any intention to repay, or when he is insolvent, or purchases goods on credit without any intention to pay for them, there is fraud. If, there is no such bad intention at the time of making contract, but the promise doesn’t perform the contract, it doesn’t amount to fraud.

ANY ACT OR OMISSION WHICH THE LAW DECLARES AS FRAUDULENT [section 17(4)]

Clause (4) provides that ‘any other act fitted to deceive’ will also amount to fraud. This clause is general and is intended to include such cases of fraud which would otherwise not come within the purview of the earlier three clauses.

ANY ACT OR OMISSION WHICH THE LAW DECLARES AS FRAUDULENT [section 17(5)]

According to this section 17(5), fraud also includes any such act or omission as the law specially declares to be fraudulent. In such cases, the law requires certain duties to be performed, failure to do which is expressly declared as a fraud.

In AKHTAR JAHAN BEGAM vs. HAZARILAL[7], A sold some property to B stating in the sale deed that he won’t be liable to B if he suffered any loss owing to A’s defective title. A had, earlier to this transaction, sold this property to somebody else, but didn’t inform B about it. It was held that A had committed fraud and the contract was voidable at the option of B.

Contracts on the basis of false statement:-

It is necessary that the false statement must have been made to induce the other party to enter into the contract.

In KAMAL KANT vs. PRAKASH DEVI[8], the plaintiff, Kamal Kant filed a suit against his mother, Prakash Devi and some others seeking the cancellation of the trust deed on the ground that his signature to it was obtained by fraud by falsely telling him that it was the general power of attorney. The deed, in this case, was attested by the plaintiff’s father and an advocate. The plaintiff was an educated man and had all the means to know the contents of the document. Under these circumstances, it was held that there was no fraud in this case.

- If there is a patent defect in an article supplied to a buyer and the buyer has an opportunity to examine the same, neglects to do so, the supplier cannot be considered guilty of fraud for not pointing out the defect.

Statement should be meant for the party misled:-

It is necessary that the misleading statement should be meant for the party who is misled. If a person is purchasing the shares of the company on the basis of any prospectus then he can’t sue the company later on because the prospectus is meant for an original allottee of the shares by the company, not for the person like the present appellant who buys the shares from the original allottee and therefore, the promoters were not liable for fraud.

DAMAGES FOR FRAUD

Where a contract is induced by fraud, the representee is entitled to claim rescission or damages or both. He would have a remedy by way of such suit, even if restutio in integrum is not possible.

- The defendant is bound to make reparation for all the damage directly flowing from the transaction.

- In assessing such damage, the plaintiff is entitled to recover by the way of damages the full price paid by him, but he must give credit for any benefit which he has received as a result of the transaction.

- As a general rule, the benefits received by him include the market value of the property acquired but such general rule is not applicable where to do so would prevent him obtaining for the wrong suffered.

- In addition, the plaintiff is entitled to recover consequential losses caused by the transaction.

- The plaintiff must take all reasonable steps to mitigate the loss once he has discovered the fraud.

CONCLUSION:-

Fraud is essentially a question of fact and the person who alleges that has to prove the same. If the plaintiff seeks the annulment of the decree on the ground of fraud or misrepresentation, he has to specifically plead the same and mention the circumstances which can lead to the conclusion of the existence of fraud. Merely making a mention of fraud or misrepresentation in the pleadings is not enough.

MISREPRESENTATION

Section 18 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 defines misrepresentation as under:

Misrepresentation means and includes-

- The positive assertion, in a manner not warranted by the information of a person making it, of that which is not true, though he believes it to be true.

- Any breach of duty which, without any intent to deceive, gains an advantage to the person committing it, or anyone claiming under him, by misleading another to his prejudice or to do the prejudice of another claiming under him.

- Causing, however innocently, a party to an agreement, to make a mistake as to the substance of the thing which is the subject of the agreement.

Positive assertion, i.e. an explicit statement of fact by a person of that which is not true, though he believes it to be true amounts to misrepresentation. There should be a false statement made innocently, without any intention to deceive.

NOORUDEEN vs. UMAIRATHU BEEVI[9] is an illustration where the transaction was set aside on the ground of fraud and misrepresentation. The defendant, who was plaintiff’s son got a document executed from the plaintiff describing it as hypothecation deed of the plaintiff’s property. In fact, by fraud and misrepresentation, the document executed was a sale deed of the plaintiff’s property. The plaintiff was a blind man and the sale was for an inadequate consideration. It was held that such a deed which was got executed by fraud and misrepresentation, was rightly set aside.

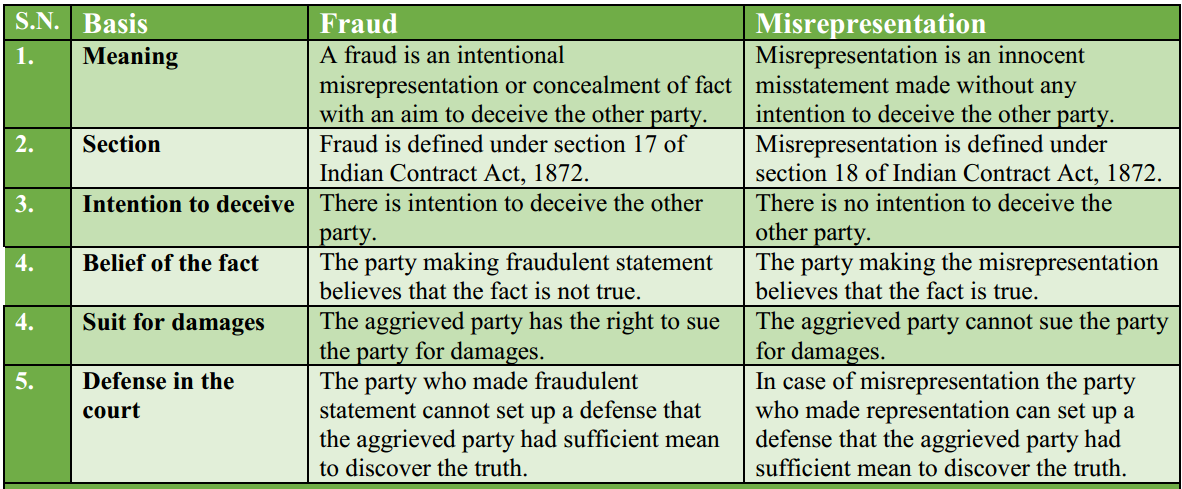

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FRAUD AND MISREPRESENTATION

| Basis | Fraud | Misrepresentation |

| 1. Believes false statement to be true | NO | YES |

| 2. Wrongful intention | YES | NO |

| 3. Claim damages under law of tort | YES | NO |

| 4. Discovering of truth by ordinary diligence | YES | NO |

CLAUSE 1

The first clause refers to a positive assertion, which apparently means an absolute and explicit statement of fact, not merely such language as to lead the hearer to infer it.

NEGLIGENT MISREPRESENTATION:-

Negligent misrepresentation is one made carelessly or without reasonable grounds for believing it to be true. But it cannot be regarded unless the representer owed a duty to the representee to be careful. The same above statement was given in the case DERRY vs. PEEK[10].

INNOCENT MISREPRESENTATION:-

The term innocent misrepresentation is used for the misrepresentation in which no element of fraud or negligence is found or one for which the representee has good grounds of belief.

In MACKENIZE vs. ROYAL BANK OF CANADA[11], a married woman stood guarantee given by her for the indebtedness of the company in which her husband was the principal shareholder. Before she stood guarantee, she was assured by her husband and the bank manager that her shares were bound to the bank and they had gone anyhow and the only chance of getting them back was if she signed the guarantee. There was a subsequent renewal of the guarantee before the plaintiff was advised of the true facts. The contract of guarantee was held liable to be avoided as induced by material misrepresentation even if innocently made. The mere fact that the party making the representation has treated the contract as binding and had acted on it didn’t preclude relief nor could it be said that the plaintiff received anything under the contract which she was unable to restore.

CLAUSE 2

In ORIENTAL BANK CORPORATION vs. JOHN FLEMING[12], Sargent J. observed:

The second clause of s. 18 is probably intended to meet all those cases which are called in the courts of enquiry, perhaps unfortunately so, cases of ‘constructed fraud’, in which there is no intention to deceive, but where the circumstances are such as to make the party who derives a benefit from the transaction equally answerable in effect as if he had been actuated by motives of fraud or deceit.

CLAUSE3

As an example of the application of this clause, the following cases may be cited.

In RE NURSEY SPINNING AND WEAVING[13], two directors, a secretary, a treasurer and an agent of the company signed a bill of exchange in the form in which the company would not be liable. The bill was sold to the bank. It was held that the company would not have been liable as a drawer. The decision proceeded on the ground that the directors, while acting within the scope of the authority, had sold the bill as one on which the company was liable, but upon which, having regard to the form in which it was drawn, the company could not be rendered liable, and the directors were, therefore, guilty of misrepresentation within the meaning of the present sub section.

DAMAGES FOR MISREPRESENTATION

Damages have always been recoverable under the English law for fraudulent misrepresentation and are recoverable for negligent misrepresentation under 2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act, 1967. Under this act, such compensation can be awarded in lieu of performance under section 19 as would place the representee in a position as if the contract were performed. The court granting rescission has also the power to order compensation under section 30 of the Special Relief Act, 1963. The person rescinding the contract would also be entitled to restitution to the extent provided in section 65.

MISTAKE

According to section 20, Mistake may work in two ways:

- A mistake in the minds of parties is such that there is no genuine agreement at all. There may be no consensus and idem i.e. the meeting of two minds, i.e. there may be absent of consent. The offer and acceptance do not coincide and thus no genuine agreement is constituted between the parties.

- There may be a genuine agreement, but there may be a mistake as to a matter of fact relating to that agreement.

Mistake, when there is no consensus ad idem or there is an absence of consent:-

“Two or more persons do not agree to the same thing in the same sense, there is deemed to be no consent on their part. In other words, there may be an absence of the meeting of minds of the parties, or there may be no consensus ad idem. In such cases, there arises no contract which can be enforced.”

In RAFFLES vs. WICHELHAUS[14], the buyer and the seller entered into an agreement under which the seller was to supply a cargo of cotton to arrive “ex Peerless from Bombay”. There were two ships of the same name i.e. Peerless and both were to sail from Bombay, one in October and other in December. The buyer had in mind peerless sailing in October while the seller thought of the ship sailing in December. The seller dispatched the cotton by December ship but the buyer refused to accept the same. In this case, the offer and the acceptance didn’t coincide and there was no contract. Therefore, it was held that the buyer was entitled to refuse to take delivery.

Mistake as to a matter of fact essential to the agreement:-

According to section 20, where both the parties to an agreement are under the mistake as to a matter of fact essential to the agreement, the agreement is void.

For example – A agrees to buy a certain horse from B. It turns out that the horse was dead at the time of bargain, neither party was aware of these facts. Hence the agreement is void.

REQUIREMENTS UNDER SECTION 20

- Both the parties to the contract should be under a mistake.

- Mistake should be as regards a matter of fact.

- The fact regarding which the mistake is made should be essential to the agreement.

MISTAKE OF BOTH THE PARTIES

Section 20 makes the agreement void if there is a mistake on the part of both the parties. For example – A and B make an agreement for the sale and purchase of a particular horse. Unknown to both the parties, the horse was dead at the time of the agreement. Since both the parties are under a mistake, the agreement is void. If the mistake is unilateral, then the agreement doesn’t get affected.

In AYEKAM ANGAHAL SINGH V. THE UNION OF INDIA[15], there was an auction for the sale of fishery rights and the plaintiff was the highest bidder making a bid of Rs. 40,000. The fishery rights had been auctioned for 3 years. The rent, in fact, was Rs. 40,000 per year. The plaintiff sought to avoid the contract on the ground that he was working under a mistake and he thought that he had made a bid of Rs. 40,000, being the rent for all the three years. It was held that since the mistake was unilateral, the contract was not affected thereby and the same could not be avoided.

MISTAKE OF FACT

There should be a mistake of fact and not of law. The validity of the contract is not affected by mistake of law.

ILLUSTRATION:-

A and B make a contract grounded on the erroneous belief that a particular debt is barred by the Indian law of limitation, the contract is not voidable. Everyone is supposed to know the law of the land. Ignorance of law is no excuse. If a person wants to avoid the contract on the ground that there was a mistaken impression in his mind as to the existence of some law while he entered into the contract, he will get no relief. For instance, A owes B Rs 1000, both A and B mistakenly thinks that the debt is time-barred and agrees that A may pay only Rs 500 to clear the debt. It is a mistake of law and the contract to pay Rs 500 is valid.

MISTAKE ESSENTIAL TO AGREEMENT

- MISTAKE AS TO THE EXISTENCE OF THE SUBJECT MATTER:-

If both the parties to contract believe in the existence of the subject matter, which in fact does not exist, the agreement would be void. The reason is that if the subject matter of the contract has already perished, there is nothing regarding which the contract is being made.

In GALLOWAY vs. GALLOWAY[16], a man and a woman executed a separation deed, both of them working under a common mistaken impression that they were married to each other. Since the fact of marriage was non-existent, the deed was held void.

- MISTAKE REGARDING QUALITY OF THE SUBJECT MATTER ONLY:-

If the parties to contract are not mistaken as to the subject matter, but only regarding its quality, i.e. when the subject matter has been clearly identified although its quality has not been, the agreement would be valid.

In SMITH vs. HUGHES[17], there was a sale of a parcel of oats by sample by A to B. B refused to accept the oats on the ground that he thought that the oats were old when in fact they were new. A claimed for damages from B. It was held that there was no mistake as to the identity of subject matter, but merely as to the age of oats. The contract, in this case, was not for the sale of old oats, but of a specific parcel, by a sample. The contract was, therefore, valid and B was liable for not accepting the goods.

- MISTAKE AS TO THE POSSIBILITY OF PERFORMANCE OF THE CONTRACT:-

It is the position when the performance of the contract is not legally possible. For instance, A agrees to take a lease of a fishery from B. If it turns out that A is himself already the tenant for life, and B has no interest which could be transferred to A, it is not legally possible for B to perform this contract. The agreement has been covered under mistake, is void.

- MISTAKE AS TO TITLE:-

Sometimes the parties may be laboring under a mutual mistake as to the title to the goods sold. The buyer may already be the owner of what the seller purports to sell. In fact, there is nothing which the seller has to transfer. The transfer of ownership is intended but the same is impossible as the buyer is already the owner. Such an agreement is void because of mutual mistake.

In COOPER vs. PHIBBS[18], A agreed to take a lease of the fishery from B. Unknown to both the parties, A was already tenant for life of the fishery rights and B had no title to the same. The agreement was set aside on the ground of common mistake.

- MISTAKE AS TO PROMISE:-

If there is a mistake because of which the promise does not reflect the real intention which was there in the proposed agreement, such an agreement would be void.

In HARTOG vs. COLINS & SHIELDS[19], there was a contract for the sale of 30,000 pieces of Argentine hare-skins. Negotiations as to price were on ‘per piece’ basis and that was in accordance with the usual trade practice. The sellers by mistake in the offer stipulated to supply at a certain rate “per pound” instead of “per piece”. A pound on an average contained three pieces of such skins. The buyer sued the sellers for the non delivery of goods. It was held that there had arisen no contract in this case, because the buyer could have noticed the mistake by the sellers contained in their offer, and because of their mistake, the seller’s intention was not properly reflected in the offer.

- MISTAKE AS TO THE IDENTITY OF THE PARTIES:-

This can be cleared through the case of CUNDY vs. LINDSAY[20]; one Blenkarn placed an order for supply of goods to the plaintiffs, fraudulently imitating signatures of other goods at an address which happened to be in the same street in which Blenkiron and co. was located. The plaintiff believed that this was an order from the reputed firm Blenkiron and co. and supplied the goods to Blenkarn. After receiving the goods, Blenkarn sold the goods to the defendants, who were acting innocently in good faith. The plaintiffs brought an action against the defendants to recover the goods contending that since there was a mistake as to the identity of the party when the plaintiff accepted the offer, there was no contract. Therefore, the defendants also did not get a good title to the goods and therefore, the defendants also didn’t get any title and they were bound to return the goods to the plaintiffs. It was held that because of mistake Blenkarn did not get any title to the goods and the transferee from Blenkarn, i.e. the defendants also did not get any title and they were bound to return the goods to the plaintiff.

- MISTAKE AS TO THE EXISTENCE OF A MATERIAL FACT

If the mistake is regarding a fact essential to the agreement, the agreement is void. But if the mistake does not relate to the existence of a material fact concerning the subject matter of the contract, the validity of the contract may not be affected thereby.

Click Here to Read Notes on Contract Law

– Nancy Garg

Campus Amicus at Legal Bites

[1] (1885) 29 Ch. 459, Indian contract act, RK Bangia

[2] (1851) 10 C.B. 591

[3] A.I.R. 1976 S.C. 376; Also see Premji Bhai Ganesh Bhai Kshatriya vs. Vice-Chancellor, Ravishankar University, Raipur, A.I.R. 1967 M.P. 194.

[4] A.I.R. 2001 S.C. 549. See also Ratan Lal vs. Metropolitan Ins. Co. ltd., A.I.R. 1959 Pat. 413.

[5] A.I.R. 1982 M.P. 242.

[6] A.I.R. 1976 S.C. 376.

[7] A.I.R. 1927 All. 693.

[8] A.I.R. 1976 Raj. 79.

[9] A.I.R. 1998 Ker. 171.

[10] (1889) 14 A.C. 337.

[11] (1934) A.C. 468 PER Lord Atkin at 475

[12] (1879) ILR 3 Bom 242 at 267

[13] (1881) 5 Bom 92

[14] (1864) 2 H & C. 906

[15] A.I.R. 1970 Manipur 16.

[16] (1914) 30 T.L.R. 531; followed in Law vs. Harragain, (1917) 33 T.L.R. 381.

[17] (1871) L.R. 6 Q.B. 597.

[18] (1867) L.R. 2 H.L. 149; Jones vs. Clifford, (1876) 3 Ch. D. 779; Allcord vs. walker, (1896) 2 Ch. 369.

[19] (1939) 3 All E.R. 556.

[20] (1878) 3 A.C. 459., RK Bangia, Indian Contract Act.

Disclaimer: This document is intended to provide information only. If you are seeking advice on any matters relating to information on this website, you should – where appropriate – contact us directly with your specific query or seek advice from qualified professionals only. We have taken all reasonable measures to ensure the quality, reliability, and accuracy of the information in this document. However, we may have made mistakes and we will not be responsible for any loss or damage of any kind arising because of the usage of this information. Further, upon discovery of any error or omissions, we may delete, add to, or amend information on this website without notice.