Cross Cultural Mediation

This article explains cross-culture mediation and the role of the mediator in cross-culture mediation to bridge the cultural gap.

This article explains cross-culture mediation and the role of the mediator in cross-culture mediation to bridge the cultural gap. Mediation is one of the types of ADR wherein the mediator helps the parties come to an agreement with each other, thus aiding them in reaching a settlement. Mediation can broadly be divided into domestic and international. Innumerable factors act as an impediment in the process of mediation, for example, the mala fide intention of the parties, language and...

This article explains cross-culture mediation and the role of the mediator in cross-culture mediation to bridge the cultural gap. Mediation is one of the types of ADR wherein the mediator helps the parties come to an agreement with each other, thus aiding them in reaching a settlement. Mediation can broadly be divided into domestic and international. Innumerable factors act as an impediment in the process of mediation, for example, the mala fide intention of the parties, language and cultural differences, differences in power, etc.

Cross-cultural mediation is an umbrella term used for mediation where the dispute is between parties from different nations with different cultural standards. There are different interpretations of the word culture. Culture according to Geert Hofstede is the “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others”.

According to Kroeber & Kluckhohn, “Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behaviour acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including their embodiment in artefacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e. historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values; culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action, on the other, as conditional elements of future action.’ “[1]

In a nutshell, culture is an abstract character that can be used to define a person’s actions in the past, present and future. Every human being identifies themselves with a particular culture. When parties in mediation have different cultural integrities, it is difficult for them to reach a common ground that would pave the way for an agreement.

Cultural differences thus act as a major impediment to the successful completion of the mediation process. The article discusses the various cultural problems that can arise while in session, the ways to bridge the cultural gap and the role of the mediator in ameliorating cultural differences.

Differences that can arise in Cross-Cultural Mediation

1. Difference in Dignity-Face-Honour Cultures

In one of the reports of the Program on negotiation at the Harvard School of Law, they brought out the various cultural aspects that affect the negotiations. They effectually divided the world into three pure cultural prototypes, i.e. ‘dignity,” “face,” and “honour” cultures and other mixed cultural prototypes. The three prototypes were assigned to the various groups of continents, which show the similar cultural bent of mind and the characteristics which they prioritized over the others.

Dignity was assigned to the United States, Canada, and Northern Europe.”In dignity cultures, people strive to manage conflict rationally and directly while avoiding strong emotional reactions. Because dignity cultures typically are supported by strong laws and markets, members tend to trust others and engage in mutually beneficial trades, a mindset that leads them to prefer a collaborative approach to negotiation.”[2]

The face was assigned to East Asian Societies such as China and Japan, which were predominantly agricultural economies.

According to the report face cultures tend to protect their reputation. They avoid direct confrontation out of the urge to safeguard their reputation and image, they suppress emotions and respect authority. They do not directly approach the negotiation but juggle offers to ensure fair-play and safeguard of reputation. They focus on the trustworthiness of the counterpart. [3]

The honour was assigned to the regions with herding economies and low population density, including the Middle East, North Africa, Latin America, and parts of southern Europe. The report mentions that theft deterrence, defense of oneself and protection of honour becomes an important aspect of their negotiation. They are aggressive with insults and are reluctant to trust the other party because of the fear of betrayal.[4]

Another prototype is that of the mixed culture, which is essentially a combination of two or more of these prototypes.

2. Difference in Low Context and High Context Cultures

Professor John Barkai, in his paper, cited Edward T. Hall, who considered that the clash of culture between low and high context culture would singularly be the reason for the problems in cross-border mediations. High-context cultures are cultures that use both verbal and implied language to communicate with each other. On the other hand, low-context cultures are the ones that communicate only through verbal language.

The researchers have found out that American, Scandinavian, German, and Swiss people use direct, explicit, low-context communication and that Asian, Indian, Mexican, and most middle eastern (with the exception of Israel), French, Spanish, and Greek people use indirect, implicit, high-context communication.

According to Israeli Professor Raymond Cohen - The high context cultures that use a nonverbal, implicit style of communication generally predominate in the states which follow the ideologies of collectivism, not individualism which is mainly predominant in the non-Western states examined like China, India, Japan, Mexico, and Egypt. It lays a particular focus on building healthy relationships; and is constantly considering factors such as status, respect, and face and evades confrontation.

The Hofstede Dimensions of Culture

The empirical studies of Dutch cultural anthropologist Geert Hofstede serve as an excellent tool in deciding the problems one faces in mediation. Geert Hofstede had devised these five indices, which are:

i. The Power Distance Index (PDI)

Divided into low, medium and high power-indexed cultures. Cultures with low indexes are countries like the U.S., Australia and Germany, which give less importance to the power structure, while Malaysia, Mexico, China, Indonesia and India, which are cultures with high-power distance indexes, give more importance to the power structure of the country. The low power-distant cultures focus on equality for all, while their counterparts consider giving importance to the ranking system while making decisions.

ii. Individualism (IDV) v. Collectivism

Individualism means the importance given to a particular individual, and collectivism means the focus of the team or the community as a whole. It clearly shows the importance that a country gives to the individual and collective conscience. High individualism countries include the U.S., Australia, Great Britain, Canada, and the Netherlands, whereas countries include many South and Latin American and Asian countries such as Guatemala, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.

iii. Masculinity (MAS) v. Femininity

In contemporary negotiation theory, masculine cultures are characteristics of highly competitive negotiators who will use strategies to bring the parties to a “win-lose” position. On the other hand, Feminine cultures are cooperative, “Win-win,” or principled negotiators, and they will use cooperative and Getting-To-Yes type negotiation strategies and tactics. Domination and showing off power is the major feature of the masculine culture.

On the masculinity dimension, Japan is one of the cultures ranked very high. On the other hand, the Scandinavian countries are among the most feminine.

iv. Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

A high uncertainty avoidance culture creates give great importance on the laws and rules to prevent the probability of risk in the future. If the counterparts in such a situation show lenient and laidback attitudes, these cultures will reduce the trust in these parties.

Low uncertainty culture, on the other hand, is normally avoided rules and is more tolerant towards opinions that are not rule-based. Normally the low-uncertainty culture does not have high-stakes involved or is too experienced in mediation. They are more readily acceptable to change and take more and greater risks.

Countries that rank high on uncertainty avoidance are Greece, Portugal, Guatemala, Uruguay and low in uncertainty avoidance are China, Jamaica, Denmark, Singapore.

v. Long-Term (LTO) v. Short-Term Orientation

“Long-term orientation cultures tend to respect thrift, perseverance, status, order, sense of shame, and have a high savings rate. Their members tend to make an investment in lifelong personal networks, what the Chinese call “guanxi.” There is a willingness to make sacrifices now in order to be rewarded in the future.

Asian countries score high on this dimension, and most Western countries score fairly low.

In a culture with a Short-term Orientation, change can occur more rapidly because long-term traditions and commitments do not become impediments to change. A short-term orientation leads to an expectation that effort should produce quick results. Although it might not seem at first obvious, a short-term orientation culture has a concern for saving face.” [5]

3. Linguistic Differences

Since language is a tool for communication, the difference in language and style of communication is the major impediment to cross-culture mediation. It is difficult to conduct a mediation in which the parties have no knowledge of the language of the opposite party. In addition to it, there is always a possibility of the fallibility of the interpreters. It takes time for such parties to build camaraderie with each other.

4. Historical Differences

Sometimes there exist disputes between the parties who belong to historically averse communities. When the parties join each other, the context of aversion in the past may pop up, resulting in animosity between the parties in the mediation. For example, the history of slavery of the blacks by the whites and the subjugation faced by the Jews at the hand of the Nazis.

Generally, in a diplomatic negotiation and mediation process, the mediator will be very cautious of the cultural differences and will tackle the issue if it ever arises with utmost diligence. But, historical differences are always a part of the dispute between the parties.

Role of the Mediator in Cross-Cultural Mediation to Bridge the Cultural Gap

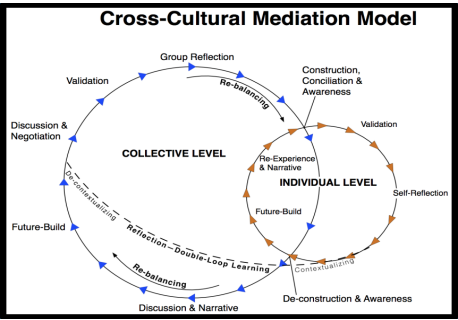

In the paper presented by Laura N. Mahan and Joshua M. Mahuna, a model was devised to be comprised of three procedures that incorporate mediator(s) into the midst of conflicted parties while guiding each individual conflicted party towards determining separate narratives:

The individual-level includes

The validation of narratives, norms and the definition of conflict, self-reflection to determine positionalities and interests, what were the determinations mechanized in this narrative to produce the current positionality (3) Future-building to seek goals beyond intermittent or gradual accommodative/integrative processing and (4) Re-experience and narrative re-construction to re-determine the new confines approached through the integral constructive processes” [6]

- The reflection – double-loop learning curve, [7]

The collective level

A mediator should identify the similarity and differences between different cultural identities and create try to frame a common-ground. Instead of focusing on the differences, you could look for common ground which would satisfy both parties.

If required the mediator can seek special interpreters to solve the linguistic problems and ensure to the parties that mediation is a trustworthy process. The mediator should try and break down the power structure and be carefully try to put aside any imbalance of power for a smooth process of conflict resolution

[1] Kroeber, A.L. and Kluckhohn, C. (1952) Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Peabody Museum, Cambridge, MA, 181.

[2] Shonk Katie. How to Deal with Cultural Differences in Negotiation. 2018, How to Deal with Cultural Differences in Negotiation, www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/business-negotiations/how-to-deal-with-cultural-differences-in-negotiation/.

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] Professor John Barkai. What’s a Cross-Cultural Mediator to Do? A Low-Context Solution for a High-Context Problem. 10 Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution 43 (2008),

[6] Laura N. Mahan Joshua M. Mahuna. Bridging the Divide: Cross-Cultural Mediation. Volume 7, Number 1, Fall 2017, Bridging the Divide: Cross-Cultural Mediation

[7] ibid

Originally Published on Aug 1, 2019

Avishikta Chattopadhyay

Institution: Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law. As a researcher, she passionately engages in contemporary legal issues and believes in law beyond books.