Act Done By A Person Under Intoxication

Act Done By A Person Under Intoxication | Overview RELEVANT PROVISIONS UNDER THE IPC, 1860 FOR ACTS DONE BY A PERSON UNDER INTOXICATION INVOLUNTARY INTOXICATION Incapable of knowing the nature and consequences of the act Without his ‘knowledge’ or ‘against his will’ VOLUNTARY INTOXICATION Presumption of Knowledge Voluntary Intoxication and Intention The article discusses the act done by… Read More »

Act Done By A Person Under Intoxication | Overview RELEVANT PROVISIONS UNDER THE IPC, 1860 FOR ACTS DONE BY A PERSON UNDER INTOXICATION INVOLUNTARY INTOXICATION Incapable of knowing the nature and consequences of the act Without his ‘knowledge’ or ‘against his will’ VOLUNTARY INTOXICATION Presumption of Knowledge Voluntary Intoxication and Intention The article discusses the act done by a person under intoxication. Some people are immune to the operation of criminal law. An act...

Act Done By A Person Under Intoxication | Overview

- RELEVANT PROVISIONS UNDER THE IPC, 1860 FOR ACTS DONE BY A PERSON UNDER INTOXICATION

- INVOLUNTARY INTOXICATION

- Incapable of knowing the nature and consequences of the act

- Without his ‘knowledge’ or ‘against his will’

- VOLUNTARY INTOXICATION

- Presumption of Knowledge

- Voluntary Intoxication and Intention

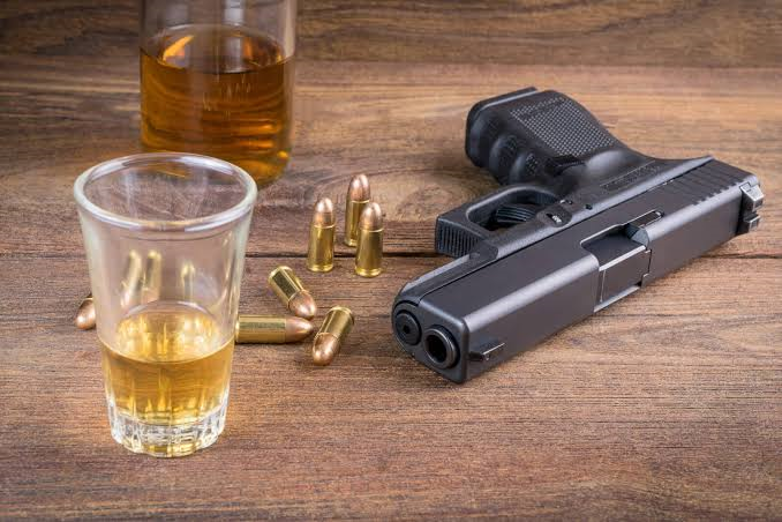

The article discusses the act done by a person under intoxication. Some people are immune to the operation of criminal law. An act done by a person under intoxication are excusable acts and ultimately exempt an individual from criminal liability.

Alcohol is closely associated with violent crimes. From the onset, the effect of alcohol on the brain is depressive. The seemingly calming effect is largely due to the fact that it destroys both the higher control centres and the other centres slowly, thus reducing or eliminating inhibitions that usually keep us within the limits of civilized behaviour. It also impairs vision, thought, and analytical capacity[2].

In the philosophy of liability, addiction presents problems. A man committing an alcohol-influenced crime may otherwise have led a normal and responsible life. His behaviour under the influence of alcohol may not represent his true character. Throughout his case, it might have been a pure deviation. It may seem unfair to prosecute a person who commits an alcohol-influenced offence like all other criminals.

I. RELEVANT PROVISIONS UNDER THE IPC, 1860 FOR ACTS DONE BY A PERSON UNDER INTOXICATION

“Section 85 in The Indian Penal Code, 1860: Act of a person incapable of judgment by reason of intoxication caused against his will – Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who, at the time of doing it, is, by reason of intoxication, incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or that he is doing what is either wrong or contrary to law; provided that the thing which intoxicated him was administered to him without his knowledge or against his will.”

“Section 86 in The Indian Penal Code, 1860: Offence requiring a particular intent or knowledge committed by one who is intoxicated – In cases where an act was done is not an offence unless done with particular knowledge or intent, a person who does the act in a state of intoxication shall be liable to be dealt with as if he had the same knowledge as he would have had if he had not been intoxicated unless the thing which intoxicated him was administered to him without his knowledge or against his will.”

IPC sections 85 and 86 describe intoxication as an extenuating element. A joint reading of ss 85 and 86 shows that the former lays out the rule on intoxication or drunkenness as a shield against a criminal charge, whereas the latter deals with a knowingly intoxicated person’s criminal liability while committing an offence under the influence of a self-administered intoxicant.

II. INVOLUNTARY INTOXICATION

Section 85 protects a man from criminal liability if, at the time the crime was committed, he was unable to realize the nature of the act or if, because of intoxication, he did something wrong or contrary to the law, given that the intoxicant caused him’ against his knowledge’ or’ against his will.’

A person seeking immunity from s 85 is required to prove that he was:

- incapable of knowing the nature of the act performed, or

- doing what was either incorrect or contrary to the statute, and

- performing the thing which intoxicated him without his consent or against his will. These are the essentials that need to be established in order to invoke Section 85.

Incapable of knowing the nature and consequences of the act

To order to be eligible for the protection of intoxication under s 85, it must be proven not only that the intoxicant is delivered against his consent or against his will, but also because of such intoxication that the person concerned was unable to comprehend the nature and consequences of the act or that what he is either incorrect or contrary to the rule.

The influence of the administered intoxicant, short of making a person unable to understand the nature and consequences of the act committed by him, does not entitle him to section 85’s protection. Likewise, a mere fact that another individual has offered him an intoxicant without his consent or against his will does not qualify him for the exclusion.

Without his ‘knowledge’ or ‘against his will’

The terms ‘without knowledge’ or ‘against will’ denote involuntary intoxication. The term ‘under his knowledge’ means that the person involved is unaware of the fact that what is ingested by him is an intoxicant or is combined with an intoxicant.

In other terms, he must be totally unaware that anything that has been prescribed or offered to him will have any intoxicating impact. Unless there is an aspect of coercion to drink the intoxicant against his will, natural persuasion serving as encouragement is not protected by the term against his will.

In Mubarak Hussain v. State of Rajasthan[3], the appellant killed his wife and five children under the influence of alcohol. The SC held that “The mere proof of intoxication is not sufficient to invoke section 85. The accused must take the plea and prove that the intoxicant was administered to him without his knowledge or against his will.”

III. VOLUNTARY INTOXICATION

A careful reading of ss 85 and 86 shows that an act carried out under the influence of self-induced intoxication amounts to a crime even if the doer is unable to recognize the nature of the act due to intoxication or that what he does is either incorrect or contrary to the law.

If voluntary drunkenness was permitted to be a protective shield from criminal liability, it would naturally result in a kind of license to commit immunity crimes. Therefore, ‘voluntary intoxication’ is no mitigation for any crime.

Moreover, section 86 deals with a self-intoxicated person’s immunity when committing an offence requiring specific information or intent on the part of an accused as a decisive component. This provides that if an offence involving such knowledge or purpose is committed by an intoxicated self-induced individual, only knowledge (and not intention) of the offence will be assumed on his part.

Section 85 covers all crimes, while s 86 covers offences that require specific intent or information. In this way, Section 86 is an exception to section 85. Nevertheless, the degree of impairment that both aspects need is the same.

A knowingly drunken person seeking protection from s 86 is required to demonstrate, like an intentionally intoxicated person seeking protection from s 85, that the degree of his addiction rendered him unable to recognize the nature of the act or that what he does is either incorrect or contrary to the rule.

In Jojomon v. State of Kerala[4], it was held that “A person is not entitled to immunity from corresponding criminal liability because, due to a self-intoxicant, he or she loses his or her mental ability to know the nature of the act or that what he or she does was wrong or contrary to law.”

Presumption of Knowledge

A person entering a state of intoxication is believed to have the same awareness as he would have had if he had not been intoxicated. For instance, if the accused was in a state of intoxication at the time of the alleged crime and the impairment is unintentional, he would be assumed to have understood at the time of the act under section 86, IPC, to have known at the time of the act that it is likely to cause death and he will be liable for punishment.

In State of Orissa v. Kabasi Suba [5], it was held that “the onus or burden shifts on the accused to prove that, on account of intoxication, he had become incapable of having a particular knowledge that he is presumed to have.”

Voluntary Intoxication and Intention

Section 86 distinguishes between intent and knowledge. It can be noted that the first part of the section is about’ intention or knowledge’ and the latter part is about knowledge only. In respect to knowledge, the law applies the same knowledge to the intoxicated man as it would have if he had not been intoxicated.

It provides for the presumption of knowledge alone, not the presumption of intent. As far as motive or purpose is concerned, it must be gathered from the case’s corresponding general circumstances, paying due consideration to the degree of intoxication.

If a man at the time of the crime committed was entirely out of his mind, it would not be possible to fix him with the necessary intention. Nevertheless, if he had not gone too far into alcohol and from the evidence, it could be seen that he had complete knowledge of the events, one could apply the rule that a man is supposed to expect the natural consequences of his act. That assumption is not disproved by the reality that he was so affected by alcohol that he readily gives in to some destructive rage.

In Mavari Surya Sathya Narayan v. State of Andhra Pradesh [6], The offender was married for 11 years with the deceased. He was an addict who often quarrelled with her. One day, after having his food, he went out and returned home with a brandy bottle, and after drinking in, he started scolding the deceased by claiming he was failing because he married his maternal uncle’s daughter.

He told her to sign on blank papers saying he was going to write on papers anything he wanted. He went crazy as she resisted and began to beat her. He caught hold of her hair as she tried to get out of the house and pulled her into the room. He pulled down the door and sought to set her on fire. She put off the flames and ran away.

The accused pulled her again, poured kerosene, set her on fire, and she was finally killed by the burns. The Andhra Pradesh HC held that “In the light of the facts, it cannot be said that the accused had suffered a total loss of mental power and therefore the provisions of s 86 would not apply.”

In Shankar Jaiswara v. State of West Bengal[7], the SC declined to invoke s 86 in favour of the defendant who, in a state of drunkenness, insulted the deceased in a filthy language and, when he was told to leave him alone, stabbed him with a sharp weapon seven times before his death, as he was not out of his senses because of intoxication.

He was conscious and capable of understanding the consequences of his behaviour. His conduct was ‘not without intention’, and the SC accordingly upheld his conviction in accordance with s 302 of the Criminal Code.

IV. Intoxication and Insanity

Intoxication can sound like insanity but the two are not the same. In both cases of ‘insanity’ and ‘voluntary intoxication’, the shield put up is the incapacity to recognize or to realize the nature of the act.

In Basdev v. State of Pepsu [8], a retired military officer was accused of murdering a 15-year-old boy. Both of them and others from the same village attended a marriage. They all went to the bride’s house for the meal. Many sat in their chairs and others didn’t.

The retired officer, who was very drunken and intoxicated, asked the young boy to step aside and leave a convenient seat for him. But the officer pulled out a pistol when the boy didn’t move and shot the boy in the stomach. The wound was fatal. The evidence showed that his voice was sometimes interrupted by the defendant and incoherent. But it also demonstrated that he could walk confidently and also speak coherently.

The evidence showed that he came to the bride’s house on his own and that he chose his own seat, and after injuring the deceased, he tried to get away from the scene and was secured a short distance from the crime scene. He realized what he had done when he was secured and asked for forgiveness.

According to the Supreme Court, all these evidence showed that the defendant had no demonstrated inability to form the intention of causing serious bodily injury in the ordinary course of nature to cause death. The court supposed, despite his inability to show this incapacity, that he anticipated the inevitable and likely effects of his act.

In other words, in the usual course of nature, he intended to inflict physical injuries on the deceased and the physical injuries thus intended to be inflicted were sufficient to cause death. The accused was found to be guilty of murder. It was also held that “ insanity, whether produced by drunkenness or otherwise is a defence to the crime charged.

In other words, voluntary intoxication operates as an extenuating factor if it leads to ‘unsoundness of mind’. The IPC makes no difference between insanity caused by habitual excessive drinking and insanity resulting from other causes. It does not deprive him of the immunity from liability only on the ground that the insanity resulted from his self-induced excessive drunkenness.”

[1] Blackstone’s Criminal Practice 2003, Peter Murphy (ed), Oxford, 2003, p 34.

[2] Glanville Williams, Textbook of Criminal Law, second edn, Stevens & Sons, London, 1983,p 464.

[3] (2006) 13 SCC 116

[4] (2011) ILR 2 Kerala 789

[5] (1978) Cr LJ (NOC) 259 (Ori)

[6] (1995) Cr LJ 689 (AP)

[7] (2007) 9 SCC 360

[8] AIR 1956 SC 488