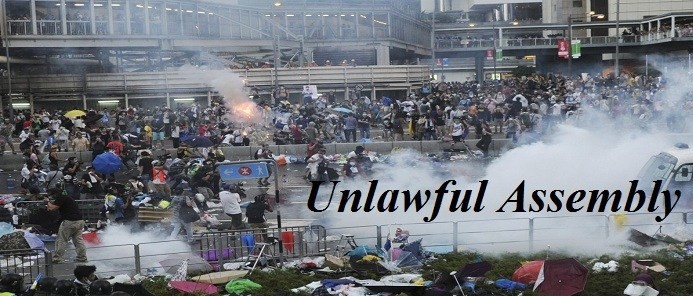

Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Public Nuisance

Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Public Nuisance | Overview Introduction Dispersal of Unlawful Assembly Meaning of Unlawful Assembly Purpose of Dispersal Procedure of Dispersal Removal of Public Nuisance Meaning of Public Nuisance Purpose of Removal of Public Nuisance Nature of Provisions related to Public Nuisance Procedure for Removal of Public Nuisance Introduction This article discusses the… Read More »

Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Public Nuisance | Overview Introduction Dispersal of Unlawful Assembly Meaning of Unlawful Assembly Purpose of Dispersal Procedure of Dispersal Removal of Public Nuisance Meaning of Public Nuisance Purpose of Removal of Public Nuisance Nature of Provisions related to Public Nuisance Procedure for Removal of Public Nuisance Introduction This article discusses the Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Pubic Nuisance. The Code of...

Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Public Nuisance | Overview

- Introduction

- Dispersal of Unlawful Assembly

- Meaning of Unlawful Assembly

- Purpose of Dispersal

- Procedure of Dispersal

- Removal of Public Nuisance

- Meaning of Public Nuisance

- Purpose of Removal of Public Nuisance

- Nature of Provisions related to Public Nuisance

- Procedure for Removal of Public Nuisance

Introduction

This article discusses the Dispersal of Unlawful Assemblies and Removal of Pubic Nuisance. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 not only provides for power and procedure to investigate a crime but also ensures that a potential crime is avoided. In respect of this object, Chapter X of the Code empowers the police and other functionaries to take actions to maintain public order and tranquillity in the society. The chapter comprises of two methods for prevention of offences and maintenance of public order.

Firstly, the power to disperse any unlawful assembly of persons and secondly, power of removal of public nuisance and dealing with persons causing such nuisance. The article shall deal with both these measures and endeavour to explain the powers and procedure under the Code with respect to these provisions.

Dispersal of Unlawful Assembly

-

Meaning of Unlawful Assembly

According to Section 141 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 an ‘unlawful assembly’ is a group of five or more persons who have one common object which may include all or any of the following:

First – To intimidate or threaten the Central Government or State Government, Parliament or State Legislature and/or any public servant during the discharge of his lawful duty by use of criminal force,

Second – To impede any law or legal process from being successfully executed,

Third – To commit any mischief or criminal trespass or any other offences under the Indian Penal Code, 1860,

Fourth – To illegally obtain any property from a person or prevent him from accessing any public way, use of water or any incorporeal right that he is entitled to,

Fifth – To threaten by use of criminal force compelling a person to do what is he is legally not bound to do or prevent from doing what he is legally bound to do.

Therefore, any group of five or more people gathered together or acting independently but towards achieving one object which is any one or more of the five objects aforementioned is an unlawful assembly. To constitute an unlawful assembly, it is not necessary that the assembly was formed with the intention to accomplish said objects but if an assembly later decides to commit an act which falls under any of the five categories, it will be considered as ‘unlawful assembly’ under Section 141 of the IPC.

-

Purpose of Dispersal

The Code grants powers to its functionaries to disperse members of such unlawful assemblies to ensure that public order and peace is maintained in the society. The provision is considered necessary because the formation of unlawful assembly and being a part of unlawful assembly has been made an offence under the IPC punishable under Section 143 and if one of the members of the assembly commit any offence towards the achievement of the common object, each member of such assembly shall be punished for that offence. Therefore, dispersal of these assemblies come under the prevention of crime and comes within the ambit of the scope of the Cr.P.C.

-

Procedure of Dispersal

The power to disperse the unlawful assembly can be exercised in three different ways under Sections 129 to 131 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

a. By Use of Civil Force: Section 129 of the Code empowers the police officers and Magistrates to command the members of an unlawful assembly or a prospective unlawful assembly (assembly of persons likely to commit any of the act under Section 141, IPC) to disperse and stop violating public peace. For the purpose of dispersal of unlawful assemblies, powers are conferred primarily on any Executive Magistrate (includes Sub-divisional magistrate and District Magistrate) or officer in charge of a police station or any officer in his absence but not below the rank of Sub-inspector.

Before any force can be used for the dispersal of an unlawful assembly, three prerequisites as mentioned in Karam Singh v. Hardayal Singh[1] should be satisfied. Firstly, there should be an unlawful assembly with the object of committing violence or an assembly of five or more persons likely to disturb public peace and tranquillity. Secondly, such assembly is ordered to be dispersed immediately by the competent authority. Thirdly, in spite of such order to disperse, such assembly does not disperse or does not, ex facie, seem to be dispersing.

The provisions under Section 129 allow the use of only civil force, i.e. command, order or warning and therefore, in a situation which did not justify firing, firing took place and that too without the orders of the authority, the dependants of the victim were ordered to be compensated by the State[2].

b. By Use of Armed Forces: In connection to the use of armed forces of the nation to disperse unlawful assembly, Section 130 of Cr.P.C provides that if the Executive Magistrate believes that the unlawful assembly cannot be dispersed by use of civil force and its dispersal is necessary for public security, such Magistrate may cause it to be dispersed by the armed forces.

The Magistrate may use the assistance of any group of persons belonging to any of the three armed forces (Army, Navy and Air Force) and with such officers under his command, he may order the arrest and confinement of persons who formed the part of such assembly. However, clause 3 provides that the armed forces and the commanding Magistrate should use as little force as required and cause minimal possible injury to any person or property.

c. By certain armed forces officers in the absence of competent authority: The provisions of Section 131 is applicable only when the public security is manifestly endangered by the presence of an unlawful assembly and when no Magistrate can be communicated with under the given circumstances. If these two conditions are satisfied than any commissioned or gazetted officer of the armed forces may use the forces under his command to disperse such unlawful assembly.

Removal of Public Nuisance

-

Meaning of Public Nuisance

An interpretation of Section 133 (1) of Cr.P.C will lead to the inference that ‘public nuisance’ includes any or all of the following acts:

First – any unlawful obstruction in any public place or from anyway, river or channel which is or may be lawfully used by the public,

Second – any trade or occupation, or any goods or merchandise, the conduct of which is injurious to the health or physical comfort of the community,

Third – construction of any building or disposal of any substance which is likely to cause fire or explosion,

Fourth – any building, tent, structure or tree that is in such a condition which is likely to fall and cause injury to persons in the neighbourhood,

Fifth – any unfenced tank, well or any excavation which lies adjacent to anyway or public place and

Sixth – any dangerous animal that may cause injury.

The above six acts individually constitute different circumstances of a public nuisance but, however, the meaning of several terms remain ambiguous since the Code is silent about them. The term “public place” in the first clause is not defined in the Code. In [3] Ram Kishore v. State, the court held that “a place in order to be public must be open to the public, i.e. place where the public has access by right, permission or usage”. Further, in Vasant Manga v. Baburao Naidu[4], the court held that “community cannot be taken to mean residents of a particular house. It means something much wider than that”.

-

Purpose of Removal of Public Nuisance

The object and purpose behind Section 133 of the code are to prevent such public nuisance which, if the Magistrate fails to take immediate recourse to Section 133, will cause irreparable damage to the public. To apply Section 133, the public nuisance should be short-term and should not have existed permanently before. Therefore, in Makhan Lal v. Buta Singh[5], the court averred that ‘no action seems possible if the nuisance has been in existence for a long period. In that case, the only remedy open to the aggrieved party is to move the civil court.

-

Nature of Provisions related to Public Nuisance

Section 133 of the code provides a rough and ready procedure for removing public nuisances and is to be used in urgent cases. The public nuisances are no doubt not as dangerous as requiring the use of security proceeding under the Code, nor their removal is as urgent as the dispersal of unlawful assemblies. However, the legislature considered that even public nuisances are fraught with potential danger. Thus, require summary action for its removal.

It is pertinent to reiterate what the Punjab and Haryana High Court observed in Bhaba Kanta v. Ramchandra[6]. The court observed that the proceeding related to the removal of public nuisances are “just to maintain peace and tranquillity and the orders rendered under these provisions are merely temporary in nature”. Basically, when there is a dispute with respect to a land between two parties, any illegal construction, etc. causes hindrances to the public as well.

Thus, the orders under any sections of removal of public nuisance come to an end when the dispute is resolved by the civil court. Hence, the orders for the removal of public nuisance are coterminous with the judgment or decree of the civil court.

-

Procedure for Removal of Public Nuisance

According to Section 133, upon receiving any reasonable information regarding the commission or omission of acts that cause a public nuisance, the appropriate Executive Magistrate can exercise his powers under Section 133.

The provision empowers the Magistrate to take evidence to support its belief that public nuisance is being committed in some part under its jurisdiction. After receiving the information and taking evidence, if the Magistrate is satisfied that one of the six circumstances aforementioned under Section 133 (1) exists, he may order the appropriate person to;

- Remove such obstruction or nuisance,

- To desist or take adequate measures to regulate the trade and occupations that are injurious to public health and safety,

- To restrain the construction of any establishment which is constructed illegally and before the decree of the civil court in that regard,

- To remove, repair or replace or otherwise fix the building or any other construction or tree which is in a falling condition,

- To fence such tank, well or excavation which is unfenced and hence, threat,

- To destroy, confine or otherwise dispose of such hazardous animals who pose a threat to the society.

To exercise the power of removal of public nuisance, the following are the sine qua non:

- The nuisance must be public and affect the members of the society as a whole and thus, can be removed from a public place,

- There must be an imminent danger to property and a consequential nuisance to the public[7],

- If the Magistrate does not take any action and direct the public to take recourse to the ordinary course of law, irreparable damage should be caused[8] and

- Obstruction or nuisance should be an invasion on the public right and on individual rights[9].

Section 134 further provides that the order passed by the Magistrate under Section 133 should be served upon the person against whom it is made by police personally and a receipt of such service should be obtained by the officer. However, the section also makes provision if the order cannot be served to the person personally.

Clause 2 of Section 134 mandates that such orders which cannot be served should be notified by proclamation and published in the official gazette or any other manner prescribed by the State Government. Also, a copy of the order must be stuck up at such place or places to ensure that the information of the order is conveyed to such person.

A person against whom such order is passed is required to adhere to the requirements of the order and remove the public nuisance in the time and manner stipulated in the order. If a person fails to perform his duties under such order, Section 135 (b) allows him to show cause for non-compliance of the order and if the person fails to show cause as well, he shall be punished under Section 136 of the Cr.P.C for an offence under Section 188 of the IPC.

References:-

- N. Chandrashekaran Pillai, R.V. Kelkar’s Criminal Procedure, (6th ed. 2018).

- Ratanlal & Dhirajlal, Commentary on the Code of Criminal Procedure, (18th 2006).

- D. Basu, Code of Criminal Procedure Vo. 1, 1973 (6th ed. 2017).

[1] Karam Singh v. Hardayal Singh, (1979) Cri. L.J 1211 (P&H).

[2] State of Karnataka v. B. Padmanabha Beliya, 1992 Cri. L.J 634 (Kant).

[3] Ram Kishore v. State, 1973 Cri. L.J 1527 (HP).

[4] Vasant Manga v. Baburao Naidu, (1996) SCC (Cri) 27.

[5] Makhan Lal v. Buta Singh, 2003 Cri. L.J 4147 (P&H).

[6] Bhaba Kanta v. Ramchandra, 1987 Cri. L.J 1155 (P&H).

[7] Kachrulal Agrawal v. the State of Maharashtra, (2205) 9 SCC 36.

[8] Vijaya Bank v. The state of Gujarat, 1999 Cri. L.J 946 (Guj).

[9] Ibid.

Ashish Agarwal

Advocate | School of Law, Christ University Alumnus